Avery

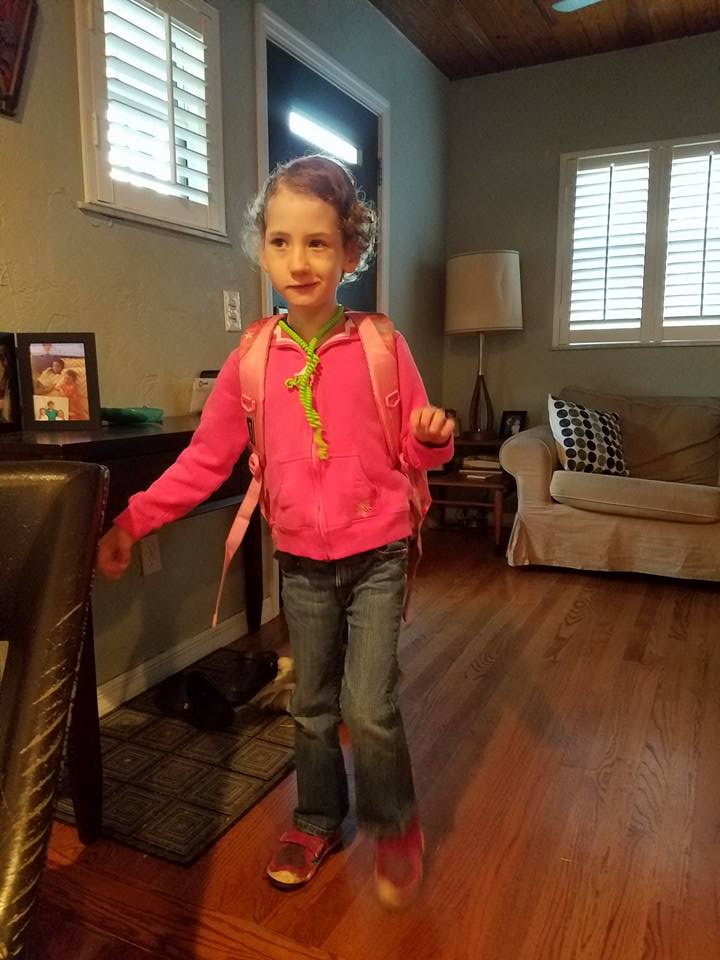

Avery Madeline Creese is six. She doesn’t know it. I want to write about her. She will never read it.

People who have been in my life know the myriad of challenges since Avery was born on April Fools Day, 2011. Nothing prepares you for the laborious, emotional roller coaster that was the process that became the effort of finding out her diagnosis. Pain and uncertainty with each negative test.

In a packet I think we got from the hospital when she was born, there was a magnet with the heading “Is your baby’s hearing on track?”

It separated the milestones by stages of their infancy – birth to 3 months, 3-6 months, 6-9 months and 9-12 months. In each section was listed what could be expected. Jumps or blinks at loud sounds. Quiets or smiles when spoken to. Responds to your voice even when you can’t be seen. Starts babbling. You get the idea.

The magnet sat on the left side of our refrigerator and with each of Avery’s milestones, I took a pen and made an impression into the magnet of a circle going around the bullet point in front of that milestone.

Avery seemed to sleep a great deal in the first month of her life. After that, the milestones started coming. Some were clearly happening. Others we would see sporadically. But I started to notice some delays. Birth-to-3 month milestones were not being met in the first three months. We thought she’s a late bloomer.

Between three and six months, I started to feel like there was no question something was wrong. Her mother had a hard time accepting what we were seeing. It was difficult. We weren’t sure what was going on.

By the time Avery turned seven or eight months, the milestones listed just stopped happening. The process began to try and discover what was going on.

The first thing I remember is a doctor suggesting she had cerebral palsy. That started the process of neurosurgeons. They referred us to neurosurgical instead of just straight neurology, so without knowing it, we were in the wrong place. Despite that, we went through the process and they were able to provide us for our first diagnoses –microcephaly (a small head) and hypotonia (low muscle tone). These were secondary diagnosis, not the source of her developmental delay. More importantly, Avery ended up getting an MRI from them and her brain activity looked fine. Cross off cerebral palsy.

We started seeing various specialists and ended up at an office that deals with all kinds of typical children’s issues. My son’s ADHD was diagnosed there. (Notably, at this time, Avery is over two years old). We met with a specialist, but she was not a doctor. I remember going through a little trial and error but at one point, she wrote down three things she thought it might be – “autism, severe intellectual disability, genetic disorder.”

She wrote the order for genetics blood tests. (Yes, tests plural. There should only have been one. Either a karyotype or microarray should have been ordered but they ordered both to our financial detriment).

So she had her tests done and we went home and rued about what it could be. I did my research and her mother did hers. We looked up different genetic disorders with the hope that if we found enough similar characteristics, maybe we could find out before the test came back. It was mentally exhausting. I went at it at home in my free time, but couldn’t find anything.

Got a call at work from Lindsay (Avery’s mom) that she thought she had found something. Told me to look up Phelan-McDermid Syndrome. I Googled it. It seemed like a match. And then I continued reading.

“Although the range and severity of symptoms may vary, Phelan-McDermid syndrome’s most common symptoms include low muscle tone (hypotonia), intellectual disability, delayed or absent speech, abnormal growth, seizures, tendency to overheat, large hands, and abnormal toenails. Affected individuals may have characteristic behaviors, such as mouthing or chewing on non-food items, decreased perception of pain, and autistic-like behaviors.”

I picked up the phone and called the doctor’s office. I asked for the person who was working with us and if results were in, maybe she would be able to tell me.

Me: “Do you guys have the test results back yet?”

Her: “Yes”

Me: “We have done some research and think we might have found it.

Her: “Really?” (Note: there are over 6,000 recognized genetic disorders)

Me: “If I ask you what it is and we are right, can we skip the upcoming appointment?”

Her: “Sure, what do you think it is?”

Me: “Phelan-McDermid Syndrome

Her, almost excitedly: “That’s it!”

Me: <head down>

I thanked her and hung up the phone. I went to our room, alone, buried my head in a pillow and bawled. I was also angry. Not about the diagnosis, but that we had hope after hope altered with each successive doctor’s appointment. With each test. All when a blood test could have been administered in utero.

For the next six months, crying out of the blue became a regular part of my life.

Avery Madeline Creese is the most difficult thing that has ever happened to me and I do not expect this to change before either she or I pass away. Simultaneously, she has done more to change me for the better than any human being who has come into my life.

I love my son Austin and other daughter Carter more than I knew I could love anything or anyone. I can tell them and they can reciprocate. I want to throw this out because sometimes, unfortunately, they are the forgotten children because they do not need constant supervision. In case they ever read this, I want to say it publicly that I am as proud as I can be of both of them. They are also great with their sister.

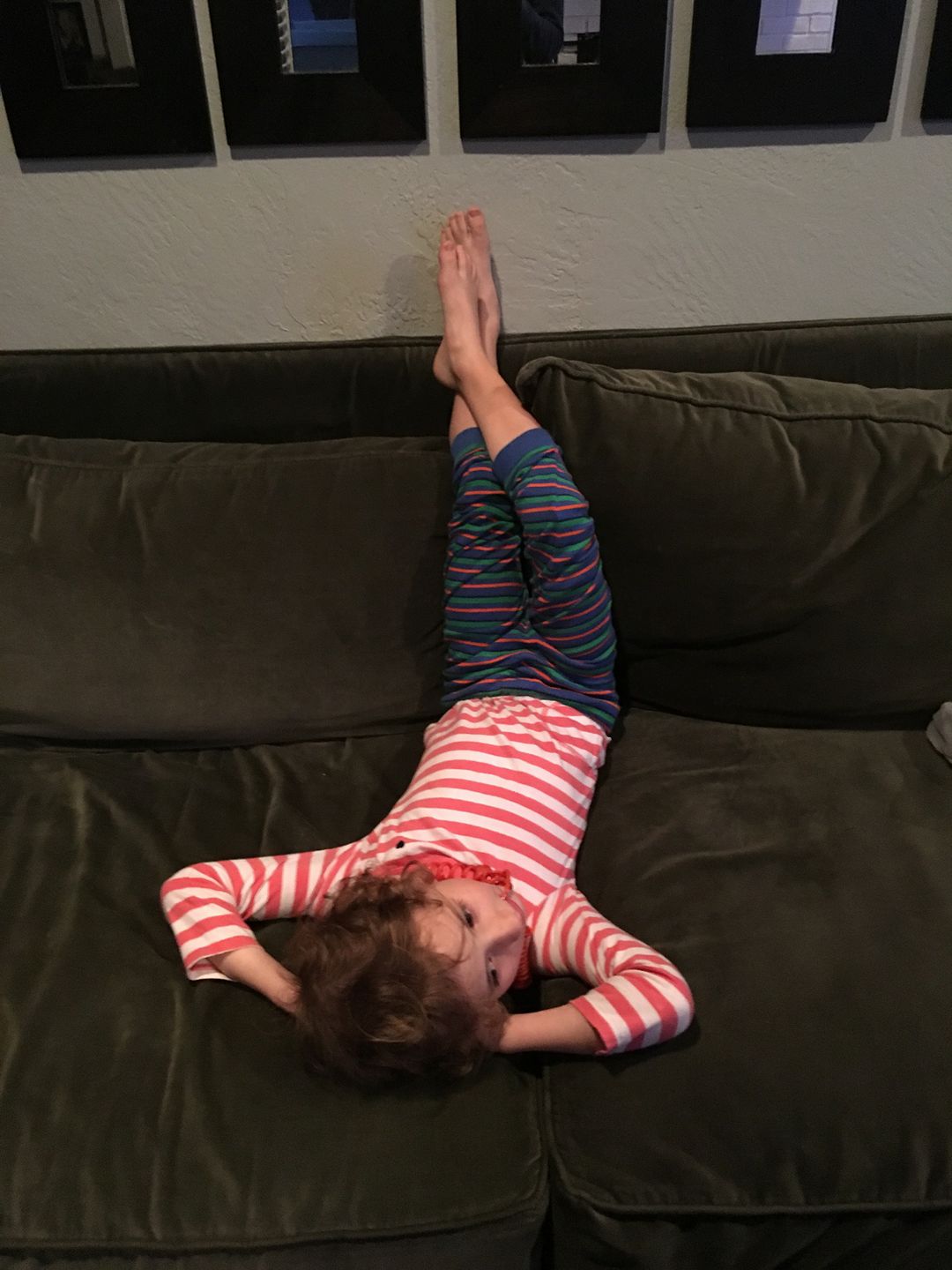

With Avery, sharing our love is less tangible. Words are replaced by eye contact. Smiles. Laughs. Hugs. Arm scratches. Our love is expressed physically. There are few things better than unsolicited love from your daughter who can not speak.

Now, if there ever comes a cure, I already have lined up what I want her to read someday:

Avery, I can not tell you how many days and nights I wished I could talk to you. I wanted tell you that you are safe with me, that there is no reason to have anxiety. No reason for fear. I wanted tell you that I will always take care of you. I’d tell you how much I love your laugh. I might have asked if we could watch a different TV channel. I want you to know that on this planet, I didn’t believe in angels, but you changed that

You are the most innocent, free, completely honest thing I have ever spent time with. I love you, your brother and sister more than anything.

You are my ‘forever baby.’ No matter your size, you will be my baby. I love your beautiful curls, the small steps of progress you make and the patience you show as we try to figure this out. Your small steps have felt as good as my life’s grandest. I will never quit for you. I may end up alone. It may be us alone. But I don’t sorry for myself.

Thank you for turning me into a better person whether I was ready or not.

Below is the end of an e.e. cummings poem I have always loved. The end was always the most confusing and my least favorite part. I always thought the poem was romantic. Now, I think its about innocence. I think its about Avery.

nothing which we are to perceive in this world equals

the power of your intense fragility: whose texture

compels me with the colour of its countries,

rendering death and forever with each breathing

i do not know what it is about you that closes

and opens;only something in me understands

the voice of your eyes is deeper than all roses

nobody,not even the rain,has such small hands

Happy Birthday to my forever baby.